I’m a bit of a romantic. That might not seem like a high-risk confession, but in my line of work—where coolheaded objectivity and calculated disruption are the norm—romanticism can make you vulnerable. Especially when it clouds judgment with the illusion of destiny. Still, I find myself drawn to the emotional undercurrents of human resilience, the stories we tell ourselves to move forward—or keep ourselves stuck.

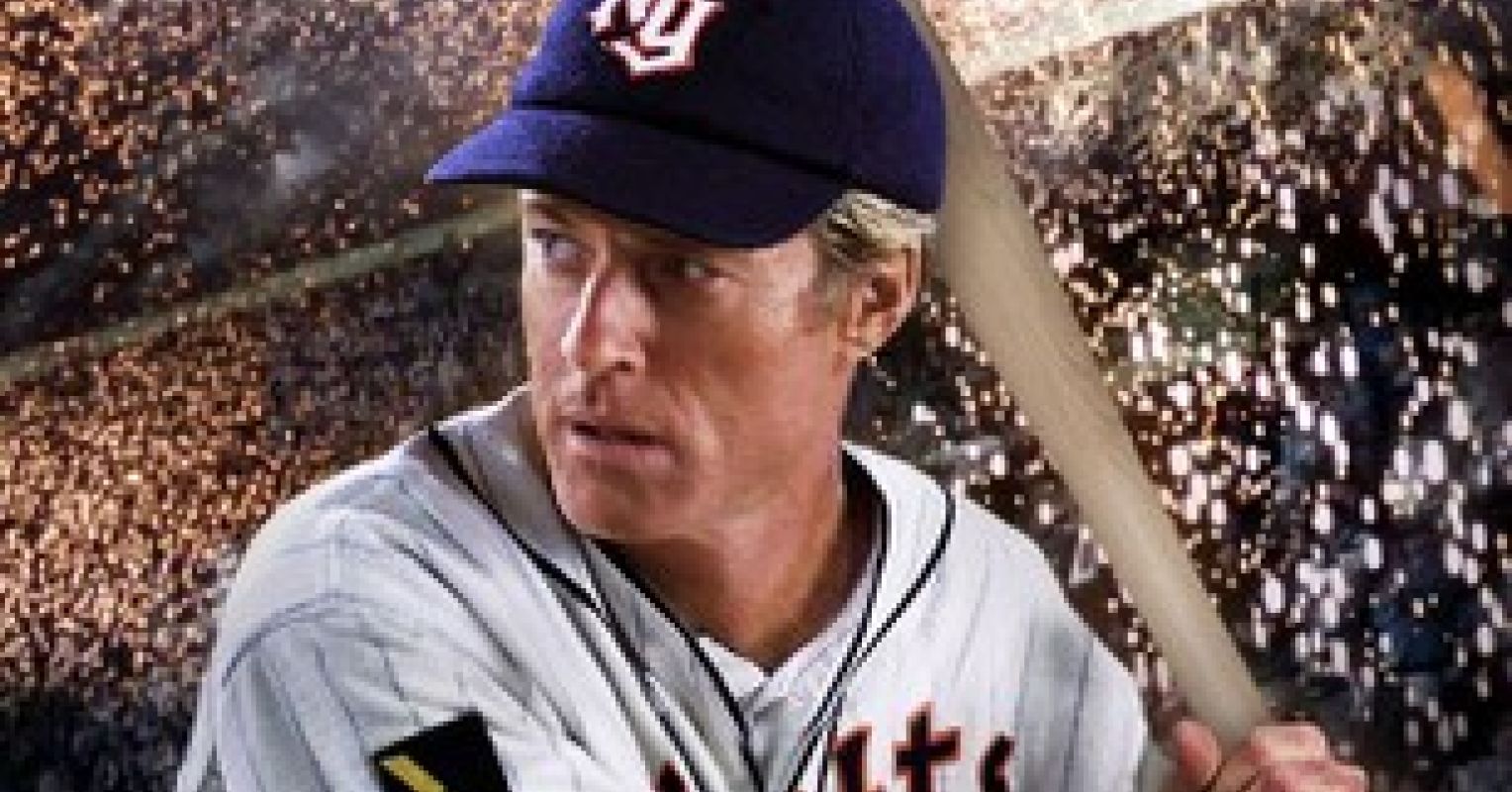

Take one of my favorite films, The Natural. It’s a romantic homage to baseball and redemption. In one of its most quoted scenes, Iris Gaines visits Roy Hobbs in the hospital and tells him, “You know, I believe we have two lives. The life we learn with and the life we live with after that.” In the film’s version of the American myth, Roy overcomes injury, returns to the field, and wins the game.

But if you read the original novel by Bernard Malamud, you know that’s not how the story ends. In the book, Roy’s career is left in ruins after being accused of throwing a game. No redemption arc. No victory. Just disgrace. It’s not just tragic, it’s Kafkaesque—a reminder that life doesn’t always reward lessons learned, or even offer closure.

Lately, I’ve been haunted by that notion of “two lives.” Why do some people seem to cross that threshold into a wiser, more adaptive second life, while others remain stuck in the first? What determines who gets to live “the life we live with after that”?

Some people do learn from failure. They recalibrate. They take ownership of the wreckage and rebuild. Others don’t. They get caught in the loop—blaming, rationalizing, railing against a system that may or may not be to blame. That’s not to say structural barriers aren’t real. They are. But so is self-deception—the myth that the “system” is always the reason we can’t move forward.

So, the deeper question becomes: Do our experiences really change our ideologies—or more accurately, our personal mythologies?

It’s tempting to turn here to social psychology or neuroscience. We know from research that people often double down on beliefs even when faced with disconfirming evidence. Cultural cognition theory shows that people interpret facts in ways that reinforce their group identity (Kahan, 2013). And trauma research tells us that adversity doesn’t automatically produce growth: Some people adapt; others struggle for years (Bonanno, 2004).

But let’s stay in the narrative for a moment.

Think of Fantine in the musical Les Misérables. In “I Dreamed a Dream,” she sings not just of heartbreak, but of collapsed meaning. She believed in a God. Then, she believed in a man. Both, she feels, abandoned her. Her tragedy isn’t just what happened to her; it’s the dissonance between what she believed and what she endured. That dissonance, unprocessed, is what ultimately destroys her.

It’s not the experience alone that breaks us. It’s the failure to revise the myth.

The Myth Gap

We all carry a personal narrative—what psychologist Dan McAdams calls a “narrative identity.” It’s the evolving story we tell ourselves about who we are, where we’ve been, and where we’re going. For some, those stories are redemptive: Mistakes are transformed into growth, suffering into strength. For others, they’re what McAdams calls “contamination stories”: A bad event spoils everything, and the story can’t move forward.

The gap between what we expected and what we experienced creates a rupture. Whether or not we learn to rewrite the story may determine whether we get a second life—or stay stuck in the first.

Learning to Rewrite

Take Robert Downey Jr., a contemporary example of someone who seemed stuck in the first life for years. There were legal troubles, addiction, a career in ruins. But somewhere along the line, the story changed. He got clean. He rebuilt. He didn’t erase the first life; he repurposed it. His success didn’t come from pretending the wreckage never happened. It came from reframing it.

Not everyone has access to the same resources or opportunities. But research does suggest that the ability to reframe personal narratives is a powerful driver of resilience. In one study, people who interpreted adversity as a challenge to grow were more likely to recover and thrive than those who saw themselves as permanently damaged (Tedeschi & Calhoun, 2004).

How the Second Life Begins

So, what does this mean in practice?

It means that change—real change—isn’t just behavioral. It’s narrative. You don’t need to rewrite your whole life story. You just need to ask different questions.

- Instead of: Why did this happen to me? try: What does this change about how I see the world—and myself?

- Instead of: How do I fix everything I broke? try: How do I grow from what I now understand?

- Instead of: Who’s to blame? try:What part of this story is mine to write next?

None of this is easy. It’s far easier to assign blame or get stuck in nostalgia. But the second life doesn’t appear on its own. It has to be written—sometimes painfully, sometimes humbly, often slowly.

The Stories We Choose

We all want to believe we’ll be the version of Roy Hobbs that hits the home run, not the one who walks away disgraced. But maybe that’s not the real dividing line. Maybe the difference isn’t between winning or losing, but between finishing the story or staying trapped in the first chapter.

The second life begins not when everything is resolved, but when we start to make meaning from the unresolved.

Because in the end, the story you tell yourself about what happened—and what it meant—may be the most powerful force in determining what happens next.