Saying “yes” can feel good, both for the speaker and listener, but being someone who is always “happy to help” can quickly lead to burnout and overwhelm. Saying yes too often can leave little time for self-care and can ultimately reduce your productivity and the quality of your contributions, leaving everyone feeling dissatisfied.

Researchers put forth boundary-setting as “a shield against being exploited” in which “‘Yes’ becomes a commodity.”1 While being happy to help can feel like a selfless thing to do, it can also be helpful to pass the opportunity to contribute along to someone else who might benefit from the task, creating more equity.

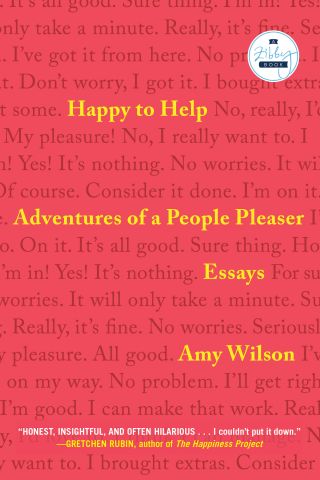

Amy Wilson, podcast co-host, author, and actor, knows firsthand how empowering saying no can feel after being a self-identified people-pleaser since childhood. In her book, Happy to Help, she humorously explores her journey as a recovering people-pleaser, and what she’s learned along the way.

Wilson shared her insights on people-pleasing with me.

Are women specifically conditioned to become people-pleasers? “Put others first” and “look like you have it all together” are messages that we often receive from society. How does this particularly impact women?

Amy Wilson: Women constantly receive those sorts of messages from society—and as I discuss in the book, we tend to receive those messages in return at the moments when we ask for help. It’s when we finally admit we’re struggling that we are most likely to be met with a platitude inviting us to change our mindset, to get a sense of humor, to stop making things harder than they need to be, to stop being so rigid or perfectionistic.

The thing is, that messaging usually isn’t helpful — or even applicable — to the actual situations that we’re struggling with. If I have a sick kid and a sick parent at the same time, I’m not a workaholic. I’m just overwhelmed. And when women ask for support and get bumper-sticker sayings in response, and when it doesn’t seem anyone around us is willing to do more, it can feel like we have no choice other than to keep handling it all ourselves.

Why do you think it is so difficult for women to say no?

AW: We’re not supposed to say “no.” In my own life, I grew up as the oldest child in a large family, which meant I was changing diapers and babysitting for free when I was still in grade school. I honestly enjoyed helping out, and I was proud of being good at it, but it was nonetheless a daily version of the messaging most women receive from a very young age: we are supposed to be helpers whenever possible, we are supposed to be pleasant while we’re helping, and we’re not supposed to make a big deal about it.

The basic definition of people-pleasing is putting other people’s wants and needs before your own. I mean, what parent hasn’t done that? What mother hasn’t integrated that into her sense of self? Isn’t that the assignment?

And for women who do not have children, there remain the societal expectations that we’ll be caretakers of any group or meeting or board of directors, and that we’ll swallow any resentment we might feel about those expectations.

For us to say “no” or “I choose not to” is disrupting a structure we’ve all been taught from a young age. That structure isn’t imaginary, and it doesn’t exist solely in women’s minds.

How did you learn to break free from people-pleasing habits? What was the turning point in your story?

AW: “Breaking free” is not a one-and-done. It’s conditioning that we have to unwind over and over again—and not just in ourselves.

The essays in the book do plot a course where I slowly get better at knowing myself. But even in the final pages of the book, I’m in a situation where I’m being asked to take on something that is absolutely more than anyone should be asked to handle. And in that situation, when I finally speak up for myself, when I say “Please don’t ask me to do that,” it happens once again: I’m told that I’m mistaken. I can do it! All I need to do is “believe in myself.”

Now, I did need to “believe in myself” in the sense of taking care of the person I was, and finally setting the boundaries that I needed, but in this case, “believing in myself” was an invitation to over deliver in the same ways I always had before.

So I had to say “no” again. And again. These habits are not just our own. First we have to change the ways we respond; then we have to hold out for as long as it takes for others’ conditioned responses to change.

What three things did you learn along the way that readers can do today to practice healthier boundary-setting?

AW: 1. Reject the idea that you have to fix yourself first. Again, that word “healthier” can cast a stigma on the person who is overwhelmed. What if that person isn’t “unhealthy” for having done more than her share? What if it’s the situation that’s unhealthy? If that’s true, okay, fix the situation—but do that without first beating yourself up for being someone with more to do than you can reasonably handle.

2. Saying “no” is only the first step. If you’ve traditionally taken on more than your share, people aren’t going to stop asking you to keep doing just that. Saying “no” is just the first step in an extended dance of renegotiation with partners who may be completely confused or disincentivized to respond. Saying “no” isn’t as uncomfortable as the silence which may follow.

3. Don’t give up too quickly. When I asked for more help from the people around me, and didn’t immediately receive exactly what I hoped for, I thought that meant there was no use in trying to do things differently. But all I had to do was stay the course, and sit through the uncertainty that occurs when you ask for change. No one is sure what will happen next. That doesn’t mean that change isn’t coming. That doesn’t mean that getting what you need will never be possible.

What do you hope readers take away from spending time with your book, Happy to Help?

AW: That when we are in difficult seasons of life, they are hard because they are hard, not because there’s something wrong with us. They are hard because they are real, not because we make things harder on purpose.

And that for even the happiest of helpers, there are some things that can never be fixed—but when there is something that needs to be fixed, it might be something besides yourself.