When I was a college teacher, I frequently asked my students to identify a psychological discovery that took them completely by surprise, a finding they never would have predicted in advance. This post is about two amazing discoveries made by researchers at the University of Chicago who study cognition and culture.

Can Thinking in a Foreign Language Lead to More Rational Choices?

Picture yourself at a casino in Las Vegas. You come across a table with a huge sign overhead, “The Big Payoff.” In this game, a player puts $100 on the table and a mechanical device flips a coin. If the coin comes up heads, you lose your $100 bet. If the coin comes up tails, you win $250. Would you take the bet?

For economists and professional gamblers, this is a no-brainer. Take the bet! Take it as many times as you can before the casino realizes its error and shuts the game down.

For the rest of us, however, it’s not an easy choice. Sure, being $150 richer would feel good, but there’s a 50-50 chance we’ll lose a hundred bucks. Losing that much money feels really bad.

In situations like “The Big Payoff,” many people don’t take the bet. Even if they’ve correctly calculated that the odds are in their favor, they still refuse to take the risk. Why take a chance that you might lose $100 and feel miserable?

This phenomenon is called myopic loss aversion. (Myopic means short-sighted.) When faced with a choice between two options, one of which involves risk, people often forgo the opportunity to achieve a gain because the fear of losing is more intense than the joy of winning. In the words of Nobel Prize winner Daniel Kahneman, “Losses loom larger than gains,” which is why most people are risk averse.

Might there be a way to help people think more rationally about choices that carry some risk? After all, such choices abound in everyday life. Should I invest in this company? Have sex with this person? Take this “shortcut”?

In 2012, Boaz Keysar and his colleagues at the University of Chicago reported the results of an experiment in which 54 volunteers played a scaled-back version of “The Big Payoff” game. The participants were randomly assigned to play the game in either their native tongue (English) or a foreign language they spoke proficiently (Spanish).

The participants received $15 in $1 bills. In each round, they could keep one of the dollar bills or risk losing it in a 50-50 bet. If they won the bet, they would keep their dollar bill and receive an additional $1.50.

In this scenario, someone who decides to place no bets will walk away with $15. The person who bets every time, however, can expect to walk away with $18.75 (because the expected value of a single bet is $1.25 and there are 15 possible bets).

Participants who played the game in English took the bets 54 percent of the time. Participants who played the game in Spanish, however, took the bets 71 percent of the time, or 30 percent more often. They were less affected by their fear of losing money. (Remember, a professional gambler would immediately see that the game was stacked in his or her favor and take every bet.)

Keysar and his colleagues explain their findings in terms of emotional distancing. In their view, thinking in a foreign language is less intuitive and more deliberate than thinking in one’s native tongue. People think more slowly when thinking in a foreign language. And foreign words—think swear words—don’t pack the same emotional punch. For all these reasons, thinking in a foreign language can produce choices that are more rational and less emotional.[1]

Are There Cultural Differences in Perspective-Taking?

How easily can you put yourself into another person’s shoes and see the world as they see it? Would it be easier if you had been raised somewhere else?

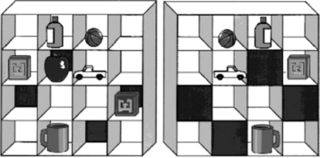

In 2007, Shali Wu and the aforementioned Boaz Keysar invited Chinese and American pairs to play a communication game that required perspective-taking. One player saw a grid in which seven objects were visible, while the other player saw the same grid but from the other side. Only five objects were visible to the second player because two others were hidden behind dark panels.

The second player (the director) instructed the first player (the actor) to “move the wooden block one slot up.” If you look closely at the grid, you’ll see there’s only one block that can be seen by both players. If the actor can easily take the perspective of the director, then the actor can immediately move the correct block, the only block that can be seen by the director. If the actor, however, isn’t adept at taking the perspective of the director, then the actor will be confused about which block to move. Being confused, the actor will either move the wrong block or take longer to move the correct block.

The Chinese participants performed at a much higher level than the Americans. They rarely made a mistake because they were more attuned to their partner’s perspective. American participants, on the other hand, often moved the wrong block, failing to adopt the mindset of their partner.

Wu and Keysar point out that everyone has the ability to take the perspective of another person, but some people use that ability more often and more naturally. In interdependent Asian cultures, the self is defined in relation to other people, so it’s especially important to consider the perspective of others. Americans, on the other hand, are taught to be independent and autonomous, so they struggle a bit when asked to see the world through someone else’s eyes.

[1] Keysar and his colleagues did a similar study with 164 Korean university students who performed the task in their native Korean or in English. That study produced very similar results.