From a psychological point of view, silence is more than the absence of sound. It is a singular mental space. Listening to your inner voice is impossible when newsfeeds, notifications, and the infinite scroll of social media constantly address you and seize your attention.

Rather than fearing silence as emptiness—which many people dread—you can shift perspective to see it as an essential mental nutrient brimming with possibility.

There is a reason why yoga and meditation aim to distance body and mind from the everyday buzz: A caesura—to borrow the musical term for a pause—is good for your neurological health and mental well-being.

One meditation aid is a kōan. A famous kōan reads: “Two hands brought together make a sound. What is the sound of one hand clapping?” The more your intellect tries to solve it, the farther it pushes an answer away. Sōtō Zen, the Serene Reflection School of Buddhism, says, “Just sitting is the essence of pure Zen.” Just sitting with eyes open, trying neither to think nor not to think (closing the eyes invites daydreaming), is the natural kind of silence that constitutes an essential nutrient.

States of absence and nonoccurrence are both physical and mental. Yet we are more likely to notice when something happens rather than take note of an event that does not happen, as in the case of Sherlock Holmes’s dog that didn’t bark. The dog didn’t wake up the household because it was familiar with the murderer, its owner; from the dog’s perspective, nothing had changed.

When Gestalt psychologist Kurt Koffka wondered why we “normally see things and not the holes between them,” he was asking why we associate objects and people with one another rather than the space that surrounds them.

This might seem an odd thought. But artists attune themselves to seeing meaningful negative spaces, pauses, and gaps. Cultural differences likewise condition what we see and hear or else fail to discern.

Consider a row of columns in front of a building or a stand of trees set in a line. Where the Western mind sees empty space between them, the Japanese mind apprehends both the physical elements and the interval, or ma, that separates them. The word “ma” translates as “gap,” “pause,” or “space between two parts.” Violinist Isaac Stern called this space “an emptiness full of possibilities . . . the silence between the notes which makes the music.”

Paying attention to sound gaps can lead to more restorative forms of silence. Unfortunately, Western minds see quiet as a negative hole, whereas the Japanese have five words to describe an aesthetic of full, voluptuous quiet.

Sabi (loneliness) is the beauty of a solitary object such as the lone ancient pine clinging to a mountainside, its branches molded by the wind.

Wabi (poverty) is the quality of things as they are, the poignancy of the simple and commonplace.

Shibui (bitterness) conjures the taste of green tea, an object reduced to its essence.

Awarē (pity) speaks to fragility and the transience of life.

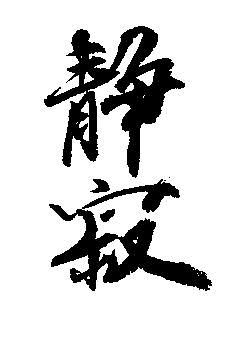

And Yugen (hidden or obscure) is the reality behind appearances, like the snowy heron hidden by bright moonlight or the vague object at the bottom of a pool. These nuances open a constellation of quiet. In the wabi-sabi ideogram the top character represents quiet, the bottom solitude. Together, the two mean “tranquility.”

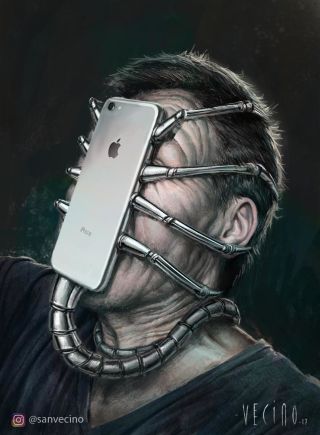

American architect Leonard Koren calls wabi–sabi the capacity to find beauty in imperfection; in that which is simple, slow, and uncluttered; in the natural cycle of growth and decline. The concept’s appeal, he suggests, lies in its ability to instill physical calm and counter the “pervasive digitalization of reality.” Fear of missing out has become our default state, he says.

“Today being an American requires being tethered to digital gadgets,” the “de facto national policy. Is it an absurd way of life? I think so.”

Japanese cinema often calls on the five concepts of quiet to emphasize the simplicity of everyday life. In films such as Tokyo Story or Spirited Away, scenes of pouring tea or walking through a forest can be as crucial to a story’s essence as a lightsaber duel is in a Star Wars film.

The books of Yasunari Kawabata, especially Snow Country, are likewise good places for American minds to learn how to see elements that otherwise seem foreign or simply not there. Can the digital world be said to have wabi-sabi traits, or is making oneself quiet wholly an inside job? The stone-age brain has always known periods of mental stillness, which is not the same as physical quiet or solitude.

The latter has two dimensions: staying centered amid commotion and being physically alone. People often mistake solitude for loneliness, but the distinction is crucial. Solitude has; loneliness wants. It is all the difference in the world.