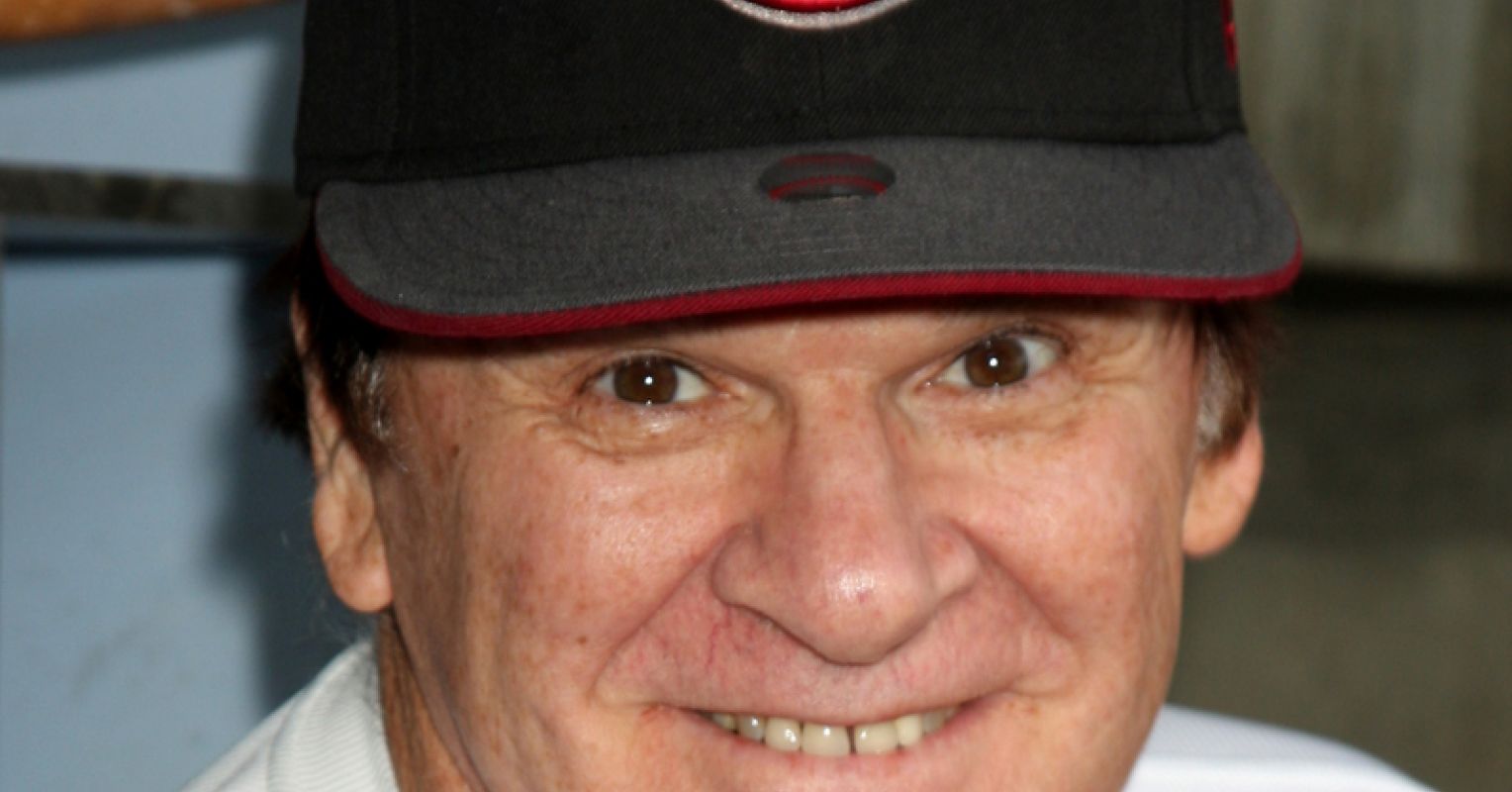

Fairness in sport again attracts the national news spotlight as an old scandal that involved Cincinnati’s star third baseman, Pete Rose, re-erupted.

One of the boldest, most durable, and naturally gifted players in the history of baseball, Rose was named Rookie of the Year in 1963 and named the National League’s Most Valuable Player 10 years later. The switch-hitter was three-times a World Series champion.

Famous for spectacular diving catches, sometimes into the stands, it wasn’t for nothing that the third baseman acquired the nickname “Charlie Hustle.” Rose was often hailed for his grit. In 1989, though, fame had begun to turn into notoriety.

A Hero’s Fall from Grace

Of course, the game’s integrity rests on the belief that games are won or lost on merit, skill, and athleticism honed diligently over a lifetime. Luck assures that no outcome is certain. Chance lures fans to wager. But the rule book forbids players and coaches from gambling, on pain of permanent ineligibility.

In 1989, rumors surfaced that Rose had routinely bet heavily on on games he played in and those he managed. The league launched an investigation. After an investigative report that ran to more than 200 pages appended with seven volumes of evidence implicated Rose in illegal activity, in accordance with the rules, the Commissioner banned him from baseball.

In 2004, after many years of denial, Rose confessed to the substance of the charges. It stretches credulity to believe that Rose did not profit from betting against his own team. The principal author of the confidential report to the Commissioner, “In the Matter of: Peter Edward Rose, Manager, Cincinnati Reds Baseball Club,” attorney John N. Dowd summarized the gravity of the findings. “Betting,” he wrote, “exposes the game to the influence of forces who seek to control the game to their own ends. Betting on one’s own team gives rise to the ultimate conflict of interest.”

Rose’s prowess was never in doubt. But in a stroke, the finding also rendered Rose ineligible for induction into the National Baseball Hall of Fame, the game’s highest honor.

Who Is a Hero?

Fandom creates sports heroes based on performance. But scan the list of baseball greats of yesteryear and you will find distinguished service elsewhere. Yogi Berra fought in the D-Day Invasion. Joe DiMaggio served in the Air Force. Ted Williams served in both World War II and Korea. Jackie Robinson broke the pernicious color barrier.

Roberto Clemente, the first Latin American player to be inducted into the National Baseball Hall of Fame, played right field for Pittsburgh for 18 years, racking up 3,000 hits.

He may yet well be remembered equally for his humanitarian efforts off the field.

Clemente founded a sports center for disadvantaged youth in Puerto Rico. When a disastrous earthquake shook Nicaragua in 1972, Clemente organized emergency relief flights. After discovering that aid had been diverted by the corrupt dictator, he boarded a cargo plane bound for Managua to monitor distribution. He died when his DC-7, overloaded with emergency supplies, crashed into the Atlantic.

Major League Baseball established an award in his name to recognize “players who best represent the game through extraordinary character, community involvement, [and] philanthropy.”

Playing by the Rules

Let’s not miss the virtues of sport itself. Playing sports routinely teaches selfless teamwork and loyalty. Sport demands dedication and encourages perseverance despite pain and inconvenience, a kind of bravery. Sport requires adaptability. Plans go sideways. Sport thus trains equanimity: You win some, you lose some.

Coaches and parents preach that winners never cheat and that cheaters never win. This conventional wisdom about personal integrity spills over into life. The moral sinks in.

Players depend upon a fair game. The game cannot proceed without playing by the rules. And fans demand it.

Sport often delivers rousing life lessons and morality tales. Few are as inspiring as Clemente’s—and rarely as stark as Pete Rose’s.

A Question of Character

For Pete Rose, always a gritty player, grittiness shaded into heedlessness. He corked his bats to get more distance. In 1973, in the third game of the National League Championship series, Rose provoked a bench-clearing brawl. Off the field Rose hung out with mobsters and strippers. He served a prison term for tax evasion. In 2003 he admitted to a past sexual relationship with a 14- or 15-year-old girl but dismissed it, saying, “Hey babe, that was 55 years ago.”

Tweets and Consequences

Fast forward two decades. In a late-night tweet on his platform Truth Social, President Trump, an adjudicated rapist who had himself evaded charges of more than 90 felonies, promised to pardon Rose for unspecified crimes.

Further, he urged Major League Baseball to “GET OFF ITS FAT LAZY ASS” and elect Rose to the National Baseball Hall of Fame. Rose died in 2023. His infractions, after all, had long passed notice. Over-zealous prosecutors had victimized this great player!

Shortly after the presidential tweet, the current Commissioner rescinded Rose’s ineligibility on the novel grounds that the rule against illegal betting did not apply to dead gamblers. Political commentator George F. Will, an amateur baseball authority who writes as the conscience of the game, asked the obvious question: “Does anyone believe that Major League Baseball would be reinstating Pete Rose if one of the president’s whims had not demanded it?”

The Zeitgeist in a Sour Mood

The United States’ past often simplifies to presidential terms. Jacksonian democracy ushered in an Age of the Common Man. Franklin Delano Roosevelt heroically set his chin against Depression and war. John F. Kennedy captured an emerging buoyant spirit. Literally to the moon and beyond, the future onward held bright prospects upward.

If the presidency is a “tuning fork” for the national temper, as the cultural critic Frank Bruni put it, our era is an “age of grievance” that got the president it wished. He notes that Donald Trump ascended to office in tune with a sour and spiteful mood that amplified a sense of persecution and a hunger for retribution. Both martyr and redeemer, Bruni writes, the once and future president “became a victor by playing the victim.”

Claiming grievance now seems a sure route to both clemency and victory. Should victimization guarantee absolution and adulation? Even despite brazen self-interest and crime? Do cheaters never win? As the pardon of Pete Rose tarnishes the conventional wisdom, George F. Will concluded that baseball had “aligned itself with the zeitgeist.”