Physics, the Head and the Brain

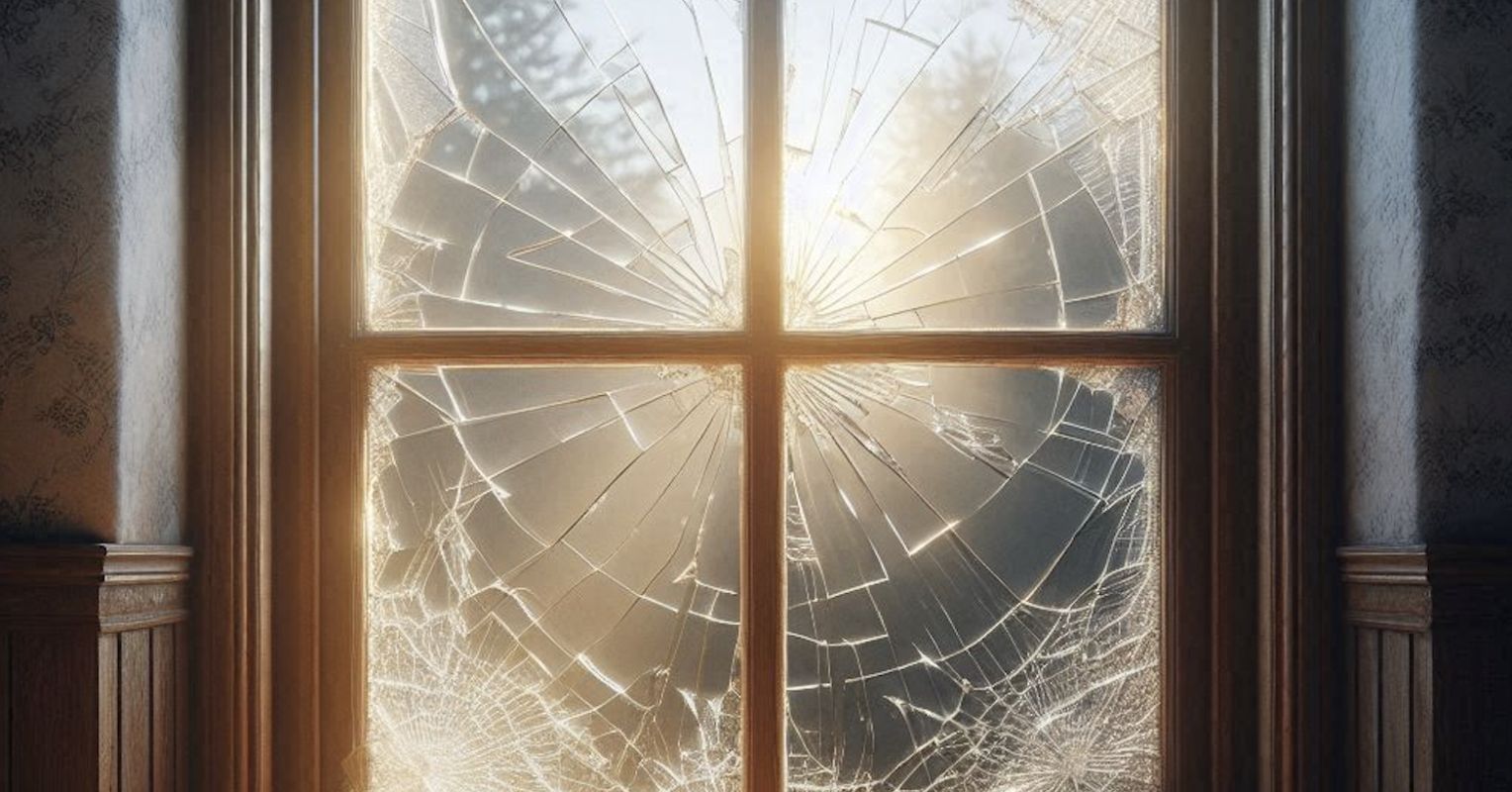

The principles of physics indicate that when an impact to the head (or a pane of glass) occurs, there is also a significant accompanying transfer of energy that reverberates and then radiates throughout the head, impacting the entire brain and the whole pane of glass.

In terms of the brain, this localised impact and the associated radiating transmission of reverberating energy can affect not only the skull the head but also penetrate deeply into the brain, disrupting neurons, synapses, transmissions, and overall brain and concomitant motor functions (Arrowsmith-Young, 2012; Doidge, 2010, 2015; Hunter, 1987; Kandel, 1999, 2006, 2013; Kimble, 1992; Roland, 2014). This indicates that an acquired brain injury (ABI) suggests that the effects of an acquired brain injury are not always as localized as initially believed (Doidge, 2010, 2015).

In children, the effects of brain trauma are particularly concerning due to ongoing brain development. Research by Bailes et al. (2013) indicates that even mild, repetitive head impacts can lead to long-term cognitive and behavioral changes in young athletes.

These findings align with studies showing that the brain of any child, youth, or adolescent is significantly more vulnerable to concussive and sub-concussive impacts, as the neural structures in these young, developing brains are still growing and are therefore very much in their neuro-developmental infancy (Giza & Hovda, 2014).

Furthermore, research by Jordan (2013) emphasizes that young boxers, particularly those under the age of 18, may face a greater risk of long-term neurological and behavioral deficits due to the cumulative effects of repeated head trauma on a developing brain. This may lead not only to structural brain damage but also to diminished cognitive function and related motor learning deficits.

In light of this evidence, concerns about boxing and other high-impact sports emphasize the importance of preventive measures, rule modifications, and increased awareness of the neurological risks associated with such activities, particularly for children (Belanger et al., 2016; Daneshvar et al., 2011; McKee et al., 2013; Montenigro et al., 2015; Patricios et al., 2018; Sullivan & Oliver, 2019).

In fact, specific to children, research strongly indicates that they should not engage in head-hitting boxing at all. Studies highlight the vulnerability of the developing brain to repetitive head trauma, with evidence showing that even sub-concussive impacts can have long-term neurological consequences (Belanger et al., 2016; Daneshvar et al., 2011; McKee et al., 2013; Montenigro et al., 2015).

While boxing training as a form of physical exercise has cognitive and physical coordination and motor learning benefits, no child should participate in activities where the head is deliberately targeted, as is inherent in boxing competitions (Patricios et al., 2018; Sullivan & Oliver, 2019).

The Benefits of Diffusion Tensor Brain Imaging

Diffusion tensor imaging can now more accurately identify what happens in the brain during a traumatic brain injury. Research indicates that brain trauma disrupts its overall functioning. This understanding arises from the fact that “axons connect different brain areas, damage to axons can cause problems in all areas, so that many functions – sensory, motor movement, cognition, and mood – are affected, regardless of where the initial impact occurred” (Doidge, 2015, p. 254). The literature now helps to better explain “why people who have had [impact trauma] to different parts of the head may have uncannily similar symptoms” (Doidge, 2015, p. 254).

The Case of Professor Pedro Bach-Y-Rita

An example of neurological and complex movement-based rehabilitation and recovery is illustrated by the case of Professor Pedro Bach-y-Rita. He was a college professor and the father of world-renowned neurologist Paul Bach-y-Rita and psychiatrist George Bach-y-Rita. In 1959, at the age of 65, Professor Bach-y-Rita suffered what was later deemed a devastating stroke, which rendered him completely incapacitated (Doidge, 2010; Hunter, 1987; Purnell, 2015).

After the medical evaluation of Professor Bach-y-Rita, the opinion communicated to Paul and George was that their father would never recover from this stroke and would remain incapacitated for the rest of his life. Once the effects of the stroke were medically stabilized, it was time for their father to leave the hospital. Professor Bach-y-Rita, in consultation with Paul, George, and the medical staff, was formally discharged into the direct care of Paul and George. Subsequently, Paul and George relocated their father from New York to Mexico to live with George.

Professor Bach-y-Rita and the Importance of Crawling

What followed next was the commencement of a rehabilitation program that was devised by George (who was a medical student at that time), and supported by Paul. “George knew nothing about rehabilitation, and his ignorance turned out to be a godsend because he succeeded by breaking all its current rules, unencumbered by pessimistic theories” (Doidge, 2010, p. 21). George based his father’s rehabilitation on that of an infant. George said:

“The only model I had was how babies learn. I decided that instead of teaching my father to walk, I was going to teach him to first crawl. I said, ‘You started off crawling, you are going to have to crawl again for a while’” (Doidge, 2010, p. 21). And so, the crawling rehabilitation began.