What humans do most is often studied least by the psychological sciences. The opposite is also true. Hypnosis has been studied a lot, yet very few of us have ever experienced deep hypnotic states (or will ever reach such states). Similarly, there is a fair amount of research on near-death experiences, yet very few of us have had, or will ever have, such an experience.

I am not denying the importance of such research, as it is critical from a social, clinical, medical and even legal perspective. But the opposite is perhaps even more interesting. On a daily basis we touch one another. We shake hands, hug, or hold hands; we’ll make sure that we match each of these touching behaviors to the right groups of our conversational partners. The psychology of touch has, however, received little attention, certainly compared to research on vision or hearing. Similarly, emotions such as sadness and fear have been studied a lot, but we know relatively little about happiness: Questions about why we laugh and what makes something funny are studied far less. Similarly, the psychology of language has extensively studied language acquisition and language disorders, but the workings of small talk, gossip, and humor—again what we are exposed to on a daily basis—are studied less commonly.

What is commonly stated about artificial intelligence is apparently also true of the psychological sciences. It’s known as the Moravec Paradox: What is easy for humans is difficult for machines, and vice versa. Approaching human reasoning requires very little computation, but approaching human sensorimotor and perception skills require enormous amounts of computational resources. In the words of psychologist Steven Pinker: “The main lesson of thirty-five years of AI research is that the hard problems are easy and the easy problems are hard.”

Analogously and equally provocatively, one could state: “The main lesson of 70 years of experimental psychology research is that rare human behavior is studied a lot and common human behavior is studied rarely.”

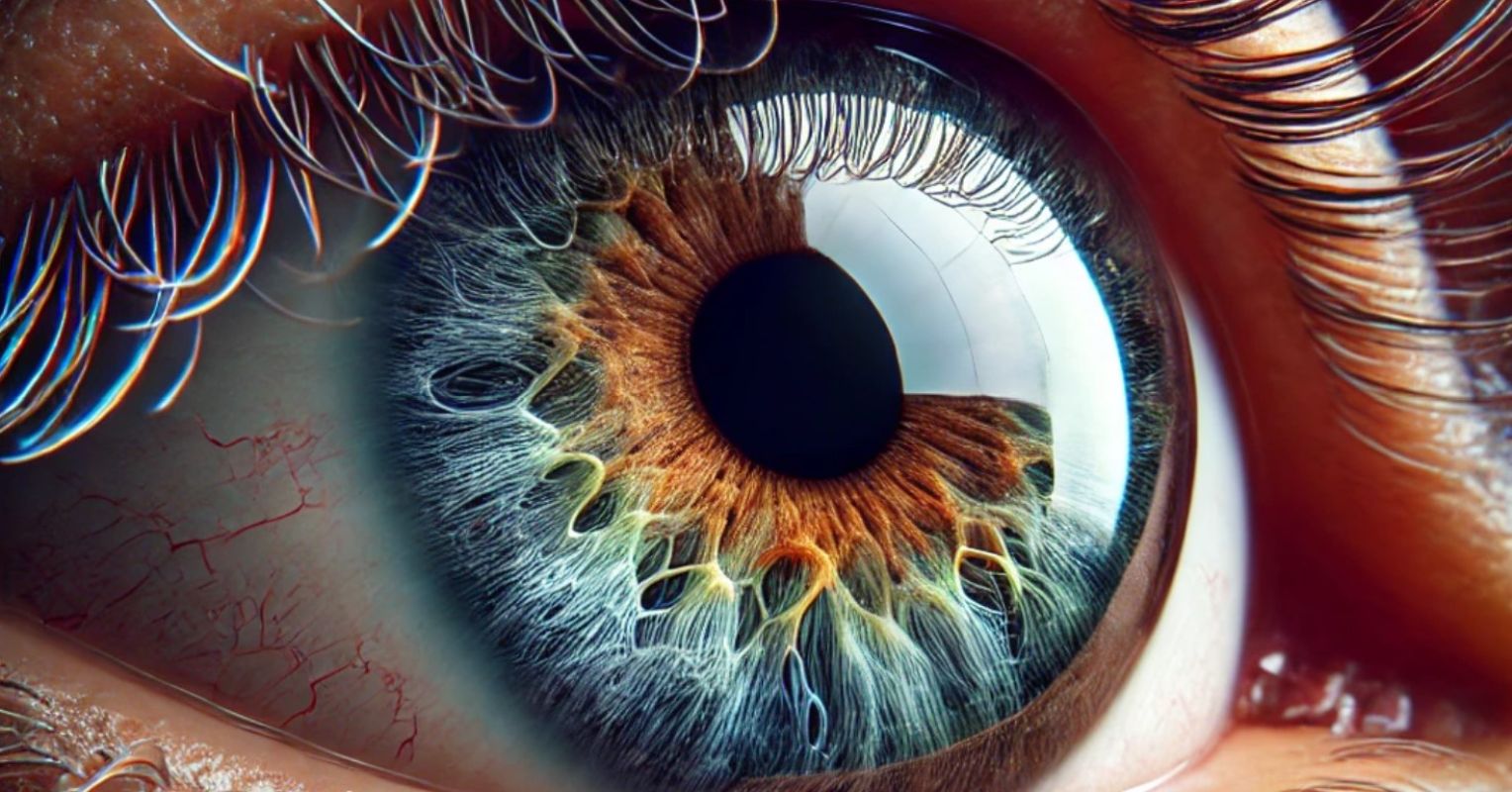

This is particularly true for a human behavior we are involved in every single day, often for many hours: making eye contact. How do you make eye contact? Are you aware of how you make eye contact?

Perhaps this question is not as critical as the question of how you should make eye contact. You can try it out yourself: Have a face-to-face conversation and make eye contact for longer than 3 seconds. An eerie feeling emerges in the social contact of you and your conversational partner. Try the opposite—not making eye contact for a while—and the contact with your conversational partner is equally awkward.

What do our eyes do when we are in a face-to-face conversation with somebody else? Over the years some psychology researchers have argued that the answer is obvious: We look at the mouth of the speaker, carefully extracting visual information that we also receive auditorily. That makes sense, but it leaves out the question how we make eye contact. Other researchers have argued that we look at the nose bridge—the area between the eyes and the mouth. The advantage is that we can make a little bit of eye contact while extracting information from the mouth. Of course, then there are researchers who argue that it is the eyes we focus on.

So, is it mouth, nose, or eyes? We recently completed an eye-tracking experiment in which we investigated this question. What we found is that when looking at a conversational partner, the eyes get the most attention by far, followed by the nose, and then the mouth. Fixation times are highest for the eyes area, followed, by a distance, by the nose and then the mouth.

The eyes apparently serve as a critical social anchor.

But that is not the entire story (and hence not the end of this post). While the eyes get the most attention when we first look at our conversational partner, attention moves toward the mouth when our partner starts to speak. The eyes seem to be a social anchor, and the mouth a communicative anchor. After our conversational partner ends the speaking event, it seems as if attention moves back to the social anchor: the eyes.

Any experimental psychologist would jump up and say: But wait, you have not really manipulated anything! Indeed, that is tricky for human conversational partners. But for non-human conversational partners—so-called embodied conversational agents that look like humans but really are not—this is not a problem at all. In a second experiment we manipulated the face of a virtual human—something we certainly did not want to do with a human conversational partner. When we disabled the action of the eyes or the mouth, we found participants looking less to the eyes and more to the mouth when the eyes were restricted, and more to the eyes and less to the mouth when the mouth was restricted. This pattern was consistent over time, with an initial bias toward the eyes, followed by an increased attention toward the mouth when the virtual human started speaking, followed by a bias back to the eyes.

Our eyes draw attention from our conversational partner, unless we are speaking; then, they compete with our mouth.

Important research? I am slightly biased. But yes, important. It’s important to understand social contact between people (social psychology, cognitive psychology, psycholinguistics) and to understand problems people have with social contact (clinical psychology). And it’s even important when building virtual humans that are supposed to behave as humanlike conversational agents.