Toward the end of Werner Herzog’s new documentary, Theater of Thought, he tells viewers that none of the 20 experts has interviewed can tell him “what a thought is.”

Herzog is delightfully curious about the “hard problem” of consciousness—how our neural activity can produce subjective experience or abstract thought, what roles our brains play in producing our thoughts and selves.

In his inimitable way, Herzog makes the subject of consciousness personal, visceral—for him and for his audiences. With neuroscientist Rafael Yuste as a guide, Herzog takes us on a listening tour, spending time with scientists whose research is on the cutting edge of consciousness studies.

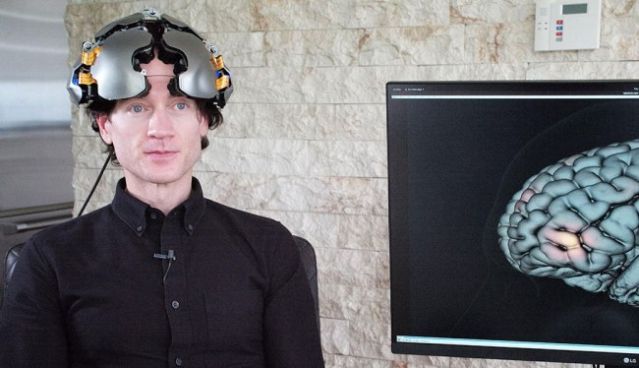

The road trip begins with Christoph Koch, a neuroscientist who studies consciousness, including its philosophical implications and practical applications. In his words, “the central mystery of the ancient mind-body problem is how does thought, how does consciousness, how does color and motion and pain and pleasure and love and hate come from this tissue?” Koch can’t answer the question, but he has collaborated on technology leaps past it. He and colleagues have developed a brain-scanning helmut that enables people who can’t speak or move to communicate through brain activity. In other words, he can’t define a thought, but his technology can read one. Koch makes the point that while the technology can only read simple communication, one day we will have “very powerful brain-mind interfaces.”

Similarly, John Donahue has developed brain-computer interfaces that can treat neurodegenerative disease, chronic pain, and depression—with the hope of treating schizophrenia one day. The result can be life-changing. Herzog films one of his patients, who shows demonstrable delight at being about to use her thoughts to control a robotic arm to raise a cup for her to drink from.

Karl Diesseroth has invented brain implants that work through light, or “optogenetics.” to control the behavior of mice. Diesseroth and his colleagues can make mice feel aggressive, social, hungry, or thirsty. Herzog asks, “Do we live in some sort of constructed fantasy world?” Diesseroth’s answer: “The Spanish writer Miguel de Unamuno actually used to speculate on this. He thought that what we think is really real is all irrational ultimately… And we construct a fake reality to protect us from the irrational… I can’t argue with that.” He tells Herzog that this research will lead to interesting technology in the future. His emphasis on interesting is a little chilling given that he’s talking created realities and mind control.

Herzog observes brain surgery with Edward Chang, an expert in implantable devices that stimulate the brains of people afflicted with neurological conditions like Parkinson’s disease. The procedure is a success. Chang is experimenting with using such devices to simulate language by “reading” brain activity in regions that produce language and using a computer interface to approximate what a person intends to say out loud but can’t. Chang explains that his research focuses on how brain activity can control speech, vocal chords, the mouth, the tongue, the breath. It’s yet one more example of the hard problem at the heart of neurological research. Though Chang’s research can produce rough simulations of speech, the “how” is beyond the grasp of contemporary science.

Joseph LeDoux, known for research on emotion, comes closer than most to addressing the hard problem. He defines the self in neurological terms, “Do we make up our lives?” His answer: “What we are doing constantly is generating a mental model of the world. Our minds are constantly narrating our lives, and that’s the story we know about our selves.” Presumably, our brains’ mental models of the world evolve with new experiences or perceptions.

Polina Anikeeva is an engineer and physicist who develops neurotechnology—tiny fibers implanted in the brain, spine, or any part of the nervous system. The fibers, theoretically, can insert electrodes for neural recording, drug delivery, and a host of other therapies. Herzog asks Anikeeva his eternal question: “Could it be in our thoughts, in our self, we are in some sort of theater of thoughts in an imaginary world?” Anikeeva’s initial response is a hesitant, “Why not?” She goes on to explain a paradox that arises from the hard problem: Our brains create realities, but these realities more or less resemble those of others—yet, we can’t experience another’s reality, so ultimately the realities our brains create are singular.

The luminaries in Theater of Thought may not be able to tell us what a thought is, but they can read and control one (or more). They can translate brain activity into language; they can use brain implants to direct mouse behavior or alleviate symptoms of Parkinson’s.

It’s not an accident that toward the end of Herzog’s tour turns to human rights lawyer Jared Genser. In Genser’s words,

I think the international community is totally unprepared for what’s coming and how fast the advances in neurotechnology are taking place… Neurotechnology is already capable of reading words that are in the human brain. And so my fear as a human rights lawyer is what happens when that technology gets more advanced?

Will courts read the minds of people accused of crimes? Or advertisers the minds of consumers? Might a dictator exert mind control on citizens? Herzog makes the point that “new facts create new norms.” Genser’s mission is to shape those norms so they “protect citizens of the world from misuse or abuse of neurotechnology. His starting point is the United Nations, but he makes the point that individual governments will need to regulate the industry—and that for any of this to happen, ordinary people will need to understand the stakes and get involved.

Chile is the first country to amend its constitution to include a neuro-ethics amendment, based largely on the advocacy of Herzog’s guide, Rafael Yuste. It’s clear that Yuste recognizes the implications of his colleagues’ incredible research. In an era when we see signs of dystopia everywhere, it’s not difficult to imagine these implications. If machine interfaces can enable humans to control external factors, the opposite is also true. These interfaces and implants may not be powerful enough yet to exert mind control, but they are headed in that direction. Herzog’s tour has left him “more mystified” about the nature of consciousness, but his film is a reminder that brain research requires not just science, but ethicists, lawyers, and poets.