In a first-of-its-kind study, the Centers for Disease Control asked teens to self-report the adversities they faced in their lives and to examine how those adversities affected them. As described in the Center’s report of October 10, 2024, the study found that not only are high schoolers today experiencing high levels of adversity, the number-one type of childhood adversity they face is at home. Sixty-one percent of teens said they experience “being put down or insulted by a parent or adult at home” (what researchers call “emotional abuse”). An equally worrisome finding of the study, Adverse Childhood Experiences and Health Conditions and Risk Behaviors Among High School Students, is that 28% of high schoolers said they live with a parent who is struggling with depression, anxiety, or another mental health disorder (what researchers call “household poor mental health”).

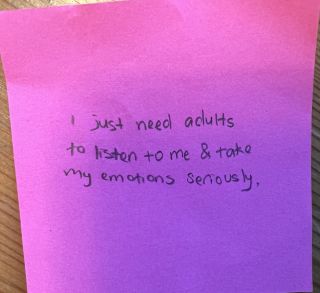

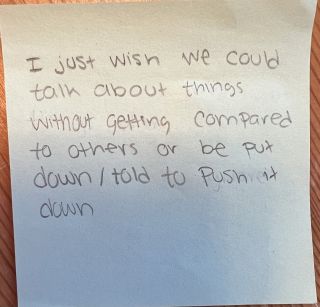

I’ve been asking teens at schools around the country what they wish they could say to their parents but can’t. This is part of my two-year-long Post-it Note Project in which teens write down their feelings on Post-it notes, expressing the things they can’t say out loud.

Notably, many teens in different parts of the country tell me that not only are they struggling, they don’t feel they have an adult they can turn to at home. They want to be able to talk to their parents, but, first, their parents need to be better regulated and calmer—parents they can count on to have their backs.

Teenagers share what they need most from their parents

Here are just a handful of the responses I’ve received to my question: “What do you wish you could tell your parents but can’t?”

“I wish the adults were more emotionally mature than the kids around them.”

“I wish we could talk about things without getting compared to others or be put down/told to push it down.”

“All the stress of you putting your problems on me is exhausting. I’m your kid, not your therapist.”

“I feel like a burden, disappointment, and failure.”

“Do not confuse my honesty with me being ‘dramatic.’ Believe me and don’t get mad when I want to tell you something.”

“I feel I can’t talk to my dad about how I feel about him b/c he takes everything so personal and he’s so combative. I don’t want our relationship to suffer.”

“I wish they wouldn’t lie to me and to each other.”

“I just need the adults to listen to me & take my emotions seriously.”

When teens feel they can’t turn to the adults in their lives with hard things without being judged, put down, made fun of, critiqued, or invalidated, there are big consequences. The CDC study found that 65% of a teen’s “persistent feelings of sadness or hopelessness were associated with experiencing one or more categories of early adversity.”

We, the adults, must upgrade our skills for regulating ourselves so we can co-regulate the young people we love so deeply. So we can be the adult who bolsters them, reassures them that they really matter, that they belong, that they are worthy, no matter what they’re going through.

Parents and children are a dyad: We can’t help one without helping the other.

Part of today’s youth mental health crisis lies in this truth: There is a disconnect between what kids want from parents emotionally and what we’re giving them. We are not meeting them where they are.

How do we start to be that person? First, we have to turn a lens on ourselves and become aware of how our own difficult life experiences have affected our levels of reactivity. Studies looking at fMRI brain scans show that the more stress and early adversity we faced growing up, the more likely we are to be reactive to stress later in life. And parenting is stressful!

A writing-to-heal exercise to build a better connection with your teen

Here’s a very quick writing-to-heal exercise to help you reflect on how you might provide more emotional safety and connection for your child.

Take a moment to get out a piece of paper and pencil.

Close your eyes. Take in a deep breath. Exhale slowly.

Now, ask yourself:

What did I want from my mother or father that I never received?

Write down whatever arises. As you write, keep your hand moving. Write faster than you normally might, as if taking dictation from your mind. Don’t worry about writing your thoughts in an organized way. Writing-to-heal exercises allow for a quick discharge of your thoughts.

The written thoughts can provide clues that will be important as you turn your lens to your own story and examine how your childhood wounds may still be affecting you now. The awareness, in turn, will enhance your ability to dial into what your child may need to receive from you.

As you do this exercise, bring a sense of self-compassion and self-love to bear on yourself and the child you once were, who might not have had the parent you needed. Many of us grew up in families where “listening” meant something else: It meant doing what parents said and complying without questioning or complaining. We may have learned that when we voiced ourselves, people would react badly or get upset with us. So we avoided voicing our feelings or needs.

Growing up in such a power dynamic can make it harder for us as adults to talk to our kids in ways that build emotional safety. Recognizing the link is essential to changing the dynamic with our children.

You can shift the vibe in your home from “I’m too stressed out and reactive to be able to help you” to one of “You belong, you matter, you’re safe with me, I will not judge you.”

Now, let’s continue reflection. Ak yourself a second question:

What do you think your child might want or need from you that they aren’t receiving?

Write down what arises here, too.

Seeing the connection between your child’s story and your story provides an Aha! moment of awareness that can help you pause and regulate yourself when stress levels are rising and your child needs your love and reassurance, not your judgment.

You simply cannot soothe your child if you are unable to soothe yourself—and that becomes impossible without first understanding what is triggering your feelings of overwhelm and reactivity. Addressing the roots of your emotions is the first step toward creating emotional safety for both you and your child.

We have to do better for our kids, and we can.