Retirement can be a jarring transition from a lifetime of extreme busyness. What does our evolutionary history say about which is better for us: working hard or taking it easy?

The Predator-Prey Divide

There is no single rule about how active animals should be for their health and reproductive success. It depends on how they make a living. Predators work little and spend long hours sleeping in the shade. Prey animals are essentially the opposite. If they are grass-eaters, they spend most of their day grazing and chewing the cud (if they are ruminants). The reason is that meat is a high-energy food whereas grass, and other herbs, are low on energy and high on fiber. This translates into long hours of chewing and digesting, leaving little time for sleep.

As hunter-gatherers, humans are both predators and vegetarians. So one might expect our normal activity level to be intermediate between predators like lions and prey like sheep. Lions typically sleep for about 16 hours a day, whereas sheep typically rest for about six to eight hours per day.

As both meat-eating predators and vegetarians, humans have a mixed activity schedule. We sleep for about eight hours, which is more than a sheep but a lot less than a lion.

The (Sad) History of Work

Humans have been extremely busy since the Industrial Revolution. The development of artificial light meant that we could work at any hour of the night or day. Welcome to the hell of shift workers!

Industrialization also brought an obsession with productivity, or the amount of product generated per hour of work. Employees had to stay busy for most of their shift if they wanted to keep their jobs.

Busyness may have come into its own with industrialization but hard work first arrived with the Agricultural Revolution. We know this from research on the agricultural transition in recent history by hunter-gatherer people such as the Agta in the Philippines (1).

When the Agta transitioned to growing their own food, they had to work harder. Taking from nature is easier than producing your own food. The Agta put in more hours of work and experienced a decline in their leisure time. So, hunter-gatherers led comparatively leisured lives. They rarely worked for more than about five hours per day, although women put in more hours than men due to their greater involvement in caring for children.

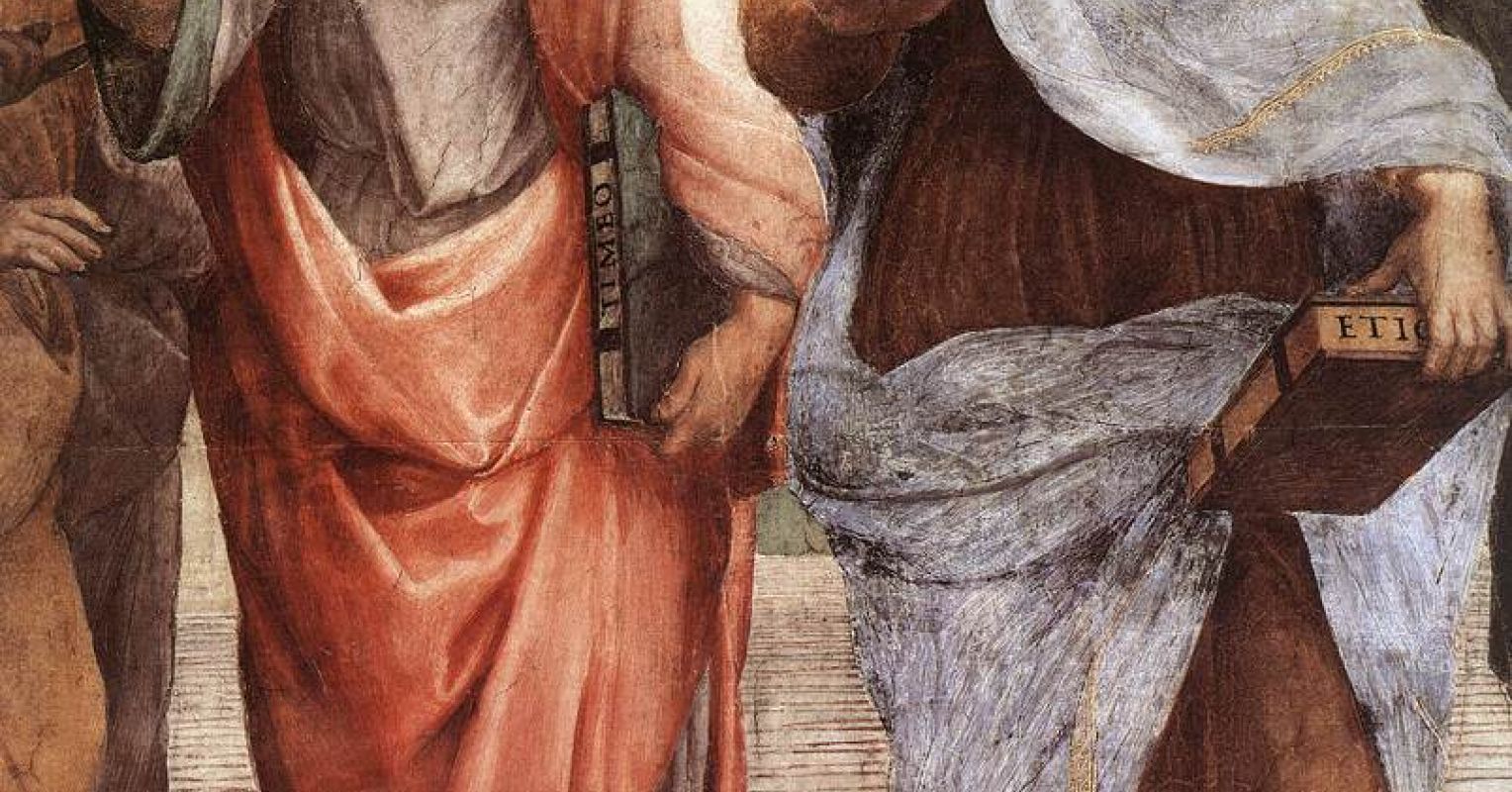

When farmers became busier, was this good for them or bad for them? There are conflicting views. The classical Greek philosopher Aristotle had a strong opinion on the issue

Aristotle’s Take

Aristotle’s take was that being active makes humans happy. As he expressed it: “Happiness is an activity of the soul in accord with virtue.”

The philosopher certainly put this maxim into practice in his own life. He was phenomenally productive as a scholar, investigating new realms of learning from embryology to literary criticism and politics.

Yet, Aristotle was part of a leisured elite and probably did not think of himself as an employee even though he served as a tutor to Alexander the Great, among other Greek nobles. He would not have appreciated busyness for its own sake. That, after all, was the life of a slave.

The connection between being active and being happy is borne out in research on clinical depression. People who remain physically as well as mentally active generally experience an elevated mood. Those who experience a depressive episode tend to be lethargic and have trouble getting up in the morning. Various therapeutic interventions aim to increase physical activity, whether by walking, or by directed activity like gardening or riding horses.

In the end, our busyness is largely determined by our subsistence economy. Farmers are busier than hunter-gatherers because producing your own food is labor-intensive and calls for long hours of work.

Is Busyness Good for Us?

Farming societies had significantly more children than hunter-gatherers. That is why there was a population explosion. In that sense, busyness was good for our Darwinian success (2). It was not good for our health, however. Inhabitants of farming societies had shorter life expectancy and they suffered from repetitive-stress injuries to the joints. They also had shorter stature, suggesting that their diet was not sufficiently varied. (Incidentally, humans could not go back to being hunter-gatherers because there is not enough space available for all of us to forage).

Workers did not fare well when they were forced to work long hours at the beginning of the Industrial Revolution. Health eventually improved, as reflected in rising stature. The health advantages were related to a variety of changes, including improved sanitation, drinking water, and public health.

They also reflected the rise of trade unions and the arrival of a much shorter work week. Our species prospered with the shortened work week. It is probably better not to work too much harder than our remote ancestors did.

References

1 Dyble, M., Thorley, J., Page, A.E., Smith, D. & Migliano, A.B. (2019), Engagement in agricultural work is associated with reduced leisure time among Agta hunter-gatherers Nature Human Behaviour, 2019 DOI: 10.1038/s41562-019-0614-6

2 Barber, N. (2023). The restless species. Portland, ME: Trudy Callaghan, Publisher.

3 Floud, R., Fogel, R. W., Harris, B., & Hong, S. C. (2011). The changing body: Health, nutrition, and human development in the Western world since 1700. Cambridge, England: NBER/Cambridge University Press.